Have you ever had a nasty paper cut that resulted in the worst pain you've ever felt?

Or maybe you stubbed your toe and that blinding “I'm going to die right now” pain shot right into your brain.

And then there's instances where people can have broken limbs or there's cases where people's knees and hips were so deteriorated that their bones were literally grinding together, and yet they didn't feel it.

Why is it that?

How can our bodies become so damaged and diseased and we are completely unaware of it?

Why is it that you can be strolling about your day, and then all of a sudden you cannot stand up straight because your spine is in excruciating pain?

What these simple differences tell us is that pain is a rich, complex experience.

Pain involves not just the physical experience of some injury (or threat of some injury), but, according to research over the past 30+ years, pain involves processing stimuli from various inputs, including social, psychological and physiological experiences.

Pain is Just Information

Research in pain indicates that the electro-chemical signals from an injury do not always say “I'm feeling pain” to the brain.

Rather, these same signals that yell at your brain “I'm in pain” today, can instead be translated as “I'm just frustrated” tomorrow.

In other words, pain is cognitive.

This means pain is interpreted by the brain using multiple streams of information – including physical, social, psychological and environmental inputs – and then decides whether the combined output says “Help, I'm in pain.”

At its most fundamental level, we can say that:

1. Pain is not the same thing as an injury.

2. Pain takes place not at the site of injury, but in the brain.

Research also tells us that the brain interprets specific signals as pain when it perceives something to be jeopardizing enough to the body’s balance (homeostasis).

Likewise, the role of pain seems to be an action signal: a signal that, if perceived, means something needs to be changed to restore the body’s homeostasis.

This gives us a third point:

3. Pain is a signal to change.

One of the challenges for treating pain is that the site of pain is not always the source of pain.

In fact, the pain in your shoulder could really be due to imbalanced hips or a bad ankle!

If you felt like you could tackle the world one day, and then your “back is out” the next day, that's a big signal that you need to change something in your daily habits.

But remember, pain is simply a brain signal and doesn't necessarily tell us what is wrong with your body.

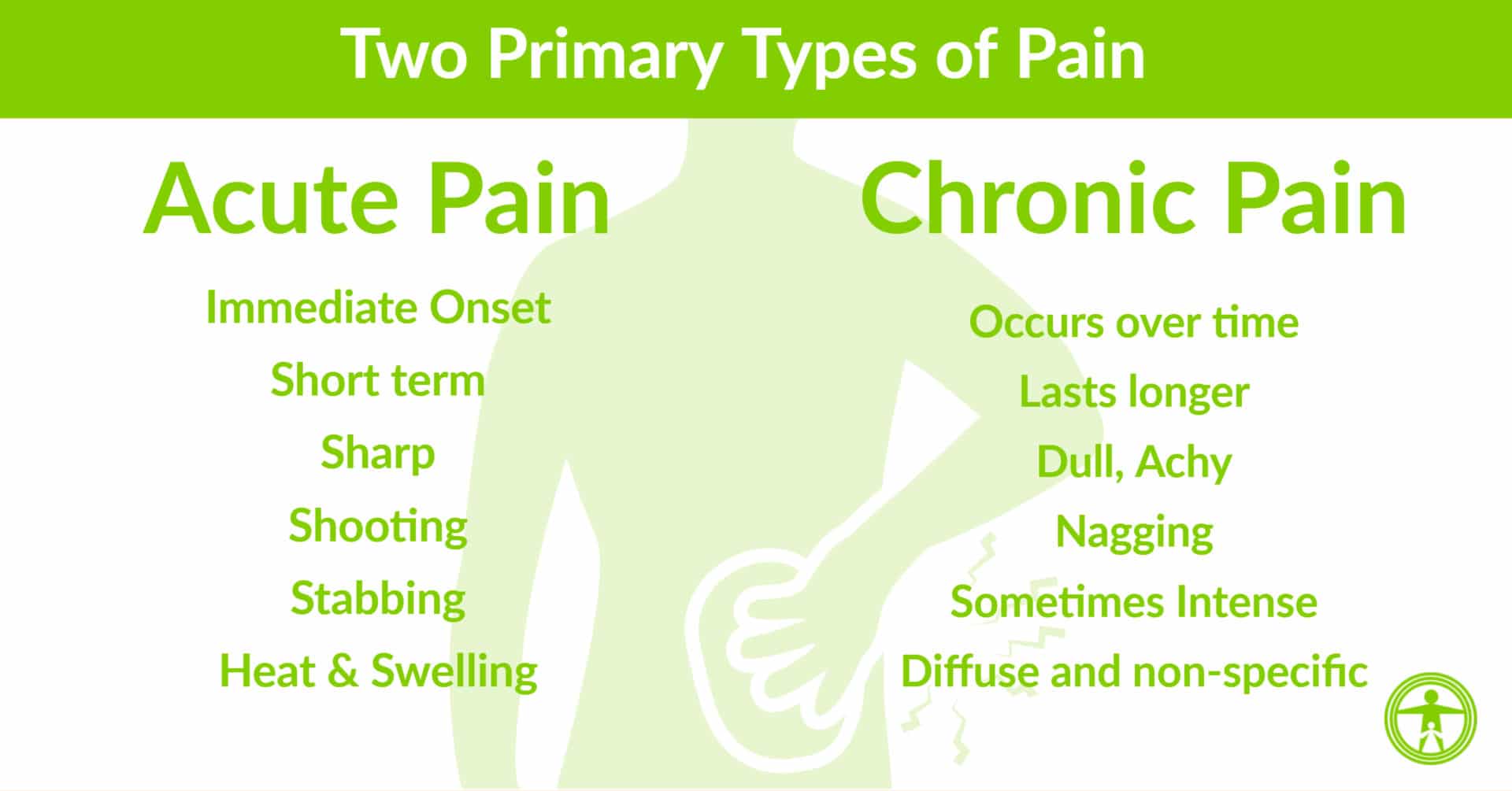

Acute (immediate) vs Chronic (long term) Pain

Generally speaking, pain breaks down into two categories: Acute and Chronic Pain.

Acute pain

According to the International Association for the Study of Pain (IASP), acute pain would be a sudden back twinge during deadlifts, or twisting your ankle on an uneven sidewalk.

Acute pain is usually going to be associated with an injury and is site specific. It could be described as “damaging pain”.

This type of pain is sharp, shooting, burning and well defined. It's also usually accompanied by swelling and heat.

Chronic pain

Chronic pain is more nonspecific and nagging. It's that pain that's been around for a year and doesn't impact you too much; but it's still a problem.

Chronic pain tends to be more diffuse. But chronic pain can be intense. Some day's your chronic pain will be at an 8 out of 10, whereas other days its down to a 1 or 2 out of 10.

The distinguishing feature is that it's not associated with an injury and changes abruptly.

People with chronic pain tend to reduce their movement (to avoid or get rid of their pain), and even fear certain types of movements; which of course causes problems.

Chronic pain can also coincide with inflammation, but there may be no physical signs that there is any particular tissue repair work going on.

All that said, in both acute and chronic pain cases, pain-free movement will always accelerate healing and break pain cycles.

Fix Your Pain by Optimizing Movement

Movement is a key signal to our bodies about how well we’re doing.

In fact, I'll go so far as saying that movement is a nutrient that your body needs to survive; just like oxygen, water and food.

We are designed as “use it or lose it” systems, constantly adapting to what we do (see Woolf’s Law for bone formation and Davis’ Law for tissue).

Abnormal movement causes wear and tear and arthritic changes to your structure (bones and soft tissue)!

Our bodies adapt to the demands — or lack of them — they experience. This is literally why exercise or strength training is so important.

If we don’t move something for a while, our bodies begin to adapt to support that lack of movement. So unused bone disappears and unused muscles atrophy.

Even things like balance and coordination will diminish if we don't practice them.

Our bodies compensate in other ways too, to make up for the lack of mobility and we often get new pain as a result of those compensations.

For instance, our joints may swell, or muscles may stiffen when asked to do work they are not designed to do.

Another example could be the pain you have in your right hip.

- If it stays there long enough, you'll start favoring your left leg to compensate.

- While this makes your right hip feel better (sort of), you eventually get pain in your left leg and hip, because you’re suddenly doing much more unbalanced work on the left hand side.

- Then, maybe your right shoulder starts to hurt, or your neck, because you’re walking around lopsided like a boat with one oar, and it’s pulling on your spine.

Here’s another common example:

Your body becomes less flexible and weaker over time (because let's face it, you don't exercise or work on yourself as much as you should).

- Your gait (or walk pattern) starts to change because your muscles are less flexible and limber

- Eventually you're not bending over or lifting things as you should.

- One night you go to bed and then wake up with severe back pain.

- This pain is the worst pain you've ever experienced and all you want to do it lay down all day.

- After a few days of lying around, you feel worse.

- Maybe your shoulders and neck start to hurt too.

- Your hips even start to hurt from the pressure of lying down.

- Eventually your pain goes away, but the dysfunctions to your neck, shoulders and hip are still there… patiently waiting

Not moving is not a great solution!

Thus, immobilizing yourself can create a vicious cycle.

Compensating for one painful movement induces other restricted movements.

But by staying as mobile as possible, moving every joint, without pain, we signal two things.

First, movement says we are still using this part of our body and thus this body part needs resources for healing and growth.

Second, the movement signals themselves can overwhelm a pain signal to say there’s more right than wrong going on in the area: there are more nerves that tell the body how we’re moving than nerves that say there’s something wrong.

Movement nerves (mechanoreceptors) are also easier to turn on than nerves that trip in the presence of noxious stimuli.

This is why you can't help but jump up and down when you hurt yourself.

Movement overcomes pain signals. It's as easy as that.

In Summary

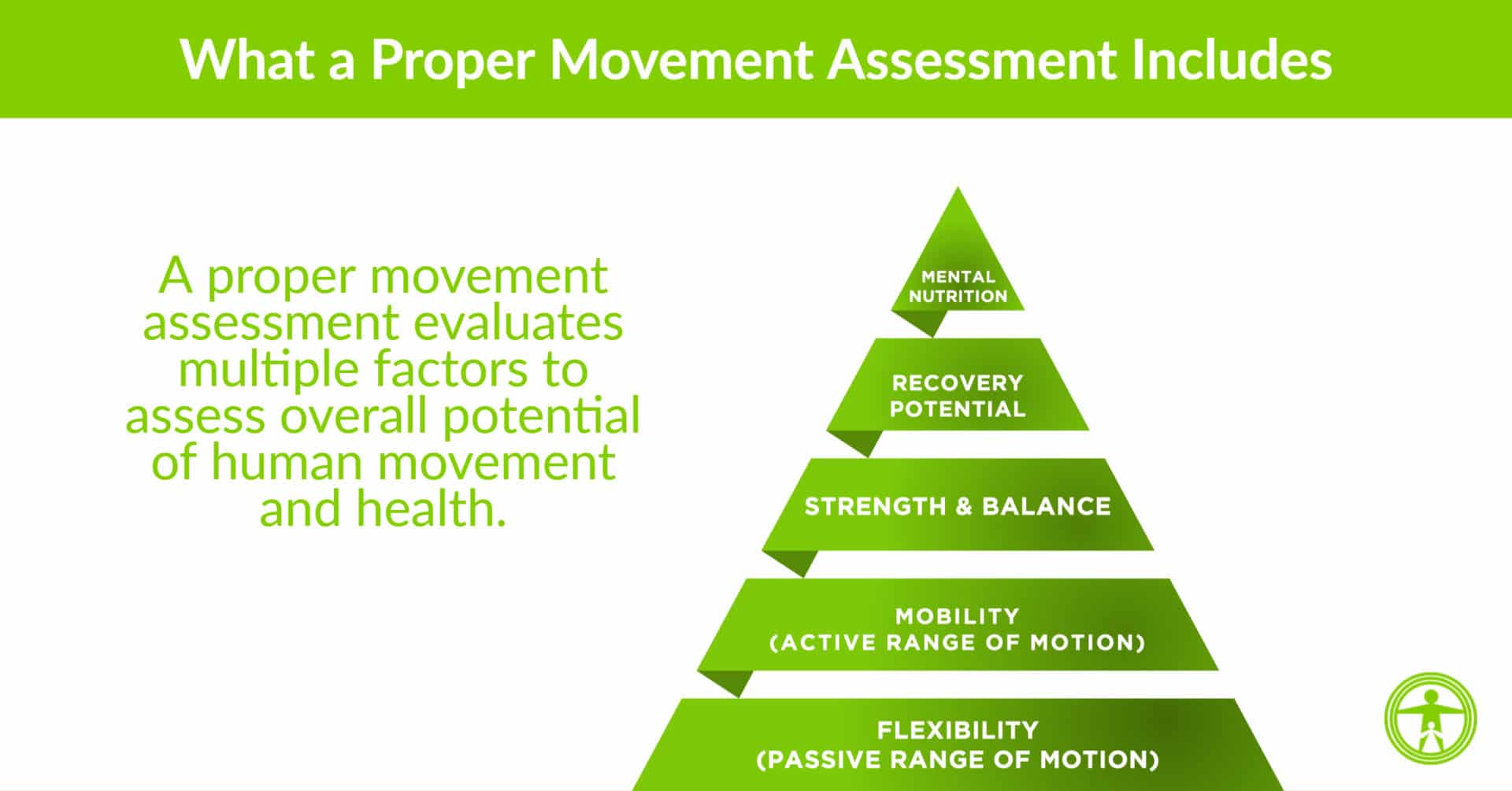

If you’ve experienced fresh or ongoing pain, it may help to seek out a movement assessment.

This means being assessed in motion.

From the bottom up, a movement assessment would evaluate ankles, knees, hips, low back, mid and upper back, shoulder and neck mobility and flexibility.

The basics of a movement assessment include a head to toe visual exam of the most basic and fundamental movements such as:

- Ankle Flexibility and Mobility

- Knee Flexibility and Mobility

- Hip Flexibility and Mobility

- Squat Mechanics

- Spine Flexiblity and Mobility

- Shoulder Flexibility and Mobility

This guidance may seem obvious, but it’s not in practice.

Many of us have seen specialists that will look at how a painful limb moves, or test our range of motion while lying on a table or standing still, but may not consider how we carry ourselves as we walk down a hallway.

Likewise, some approaches may deal only with musculo-skeletal issues.

If that works, great, but if it does not, that may be a sign that some other part of the somatosensory system is not functioning well.

This means it could be strength and balance problems or your ability to recover. There could be emotional signals and or biochemical imbalances.

But above all, pain is simply a signal to change. It means that what you're doing right now is not working.

And until the underlying issue is identified and addressed, the signal to change may keep coming.

If you're experiencing acute or chronic pain, then consider getting checked by a movement based professional who understands the complexities involved.